In my experience, the folks who have no doubts about their abilities are usually the ones that absolutely should. Enjoy this article on the Imposter Syndrome from NYT.

On paper, your investments in stocks, real estate or even cash may look like your greatest assets. While all those things are superimportant, you have something else that’s even more valuable. It’s the investment called you.

Finding ways to increase your value while doing the things you love may be the most important thing you do. Maybe you pursue more training to qualify for a raise. Maybe you find a way to sell the photography you did as a hobby. Maybe you find a way to turn your freelance writing into full-time work.

They all involve doing something new for you, but when you head down this path, you are probably going to run into this thing, this fear that you’re bumping up against the limits of your ability. Then, the voice inside your head may start saying things like:

■ “Who gave you permission to do that?”

■ “Do you have a license to be an artist?”

■ “Who said you could draw on cardstock with a Sharpie in Park City, Utah, and send those sketches to The New York Times?”

I think you get the idea. It’s at the moment when you’re most vulnerable that all your doubts come crashing in around you. When I first heard that voice in my own head, I didn’t know what to make of it. The fear was paralyzing. Every time I sent a sketch or something else into the world, I worried the world would say, “You’re a fraud.”

During a session with a business coach, I shared my fear. I was shocked when she told me this thing had a name. As you’ve tried new things or done anything outside of your comfort zone, you’ve probably felt that fear, too. The first step to dealing with this fear is knowing what to call it.

Two American psychologists, Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, gave it a name in 1978: the impostor syndrome. They described it as a feeling of “phoniness in people who believe that they are not intelligent, capable or creative despite evidence of high achievement.” While these people “are highly motivated to achieve,” they also “live in fear of being ‘found out’ or exposed as frauds.” Sound familiar?

All About the Impostor Syndrome

Listen to the Sketch Guy’s financial advice.

Once we know what to call this fear, the second step that I’ve found really valuable is knowing we’re not alone. Once I learned this thing had a name, I was curious to learn who else suffered from it. One of my favorite discoveries involved the amazing American author and poet Maya Angelou. She shared that, “I have written 11 books, but each time I think, ‘Uh oh, they’re going to find out now. I’ve run a game on everybody, and they’re going to find me out.’”

Think about that for a minute. Despite winning three Grammys and being nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award, this huge talent still questioned her success.

I’m also a big fan of the marketing expert Seth Godin, and even after publishing a dozen best sellers, he wrote in “The Icarus Deception” that he still feels like a fraud. I’ve heard that American presidents can feel this thing, too. The first time they find themselves alone in the Oval Office, they think to themselves, “I hope nobody finds out I’m in here.”

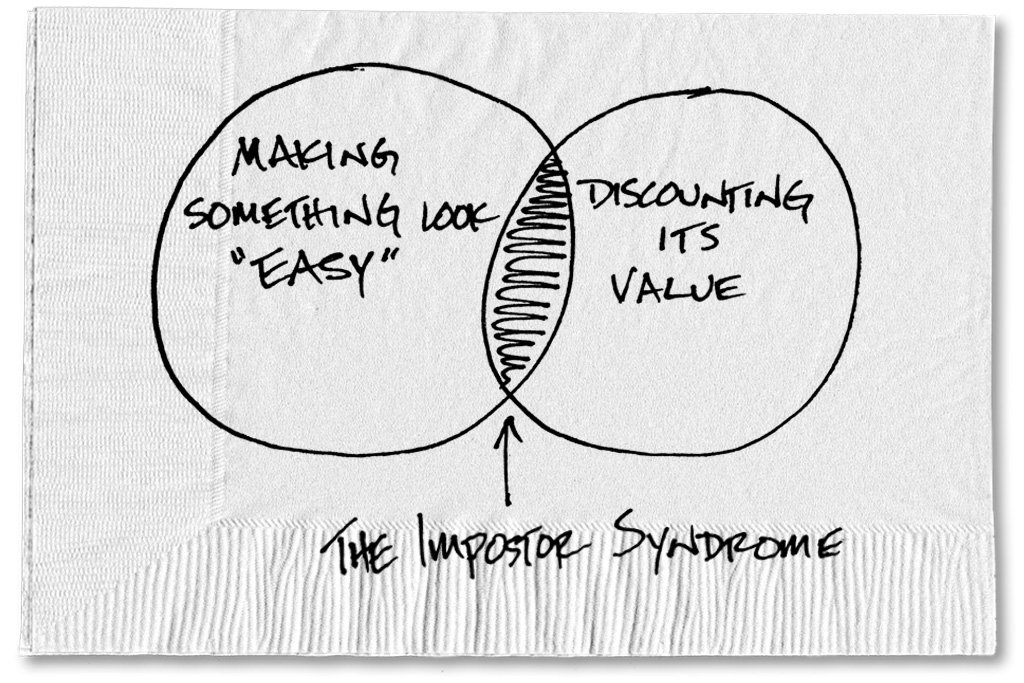

So now that we know its name and that other people deal with it too, our third step is to understand why we feel this way. I think part of the impostor syndrome comes from a natural sense of humility about our work. That’s healthy, but it can easily cross the line into paralyzing fear. When we have a skill or talent that has come naturally we tend to discount its value.

Why is that? Well, we often hesitate to believe that what’s natural, maybe even easy for us, can offer any value to the world. In fact, the very act of being really good at something can lead us to discount its value. But after spending a lot of time fine-tuning our ability, isn’t it sort of the point for our skill to look and feel natural?

All of this leads to the final and most important step: learning how to live with the impostor syndrome. I recently listened to Tim Ferriss interview the clinical psychologist and author Tara Brach. In her book “Radical Acceptance,” she shared a really cool story about Buddha and the demon Mara.

One day, Buddha was teaching a large group, and Mara was moving around the edges, looking for a way into the group. I envision Mara rushing frantically back and forth in the bushes and trees, making plans to wreak havoc. One of Buddha’s attendants saw Mara, ran to Buddha and warned him of Mara’s presence. Hearing his attendant’s frantic warning, the Buddha simply replied, “Oh good, invite her in for tea.”

This story captures beautifully how we should respond to the impostor syndrome. We know what the feeling is called. We know others suffer from it. We know a little bit about why we feel this way. And we now know how to handle it: Invite it in and remind ourselves why it’s here and what it means.

For me, even after six years of sharing these simple sketches with the world and speaking all over the world, you think I’d be used to it. In fact, the impostor syndrome has not gone away, but I’ve learned to think of it as a friend. So now when I start to hear that voice in my head, I take a deep breath, pause for a minute, put a smile on my face and say, “Welcome back old friend. I’m glad you’re here. Now, let’s get to work.”

Original POST